CGP London is pleased to announce a new installation by Sharon Kivland. Entitled Folles de leur corps / Crazy about their bodies, the installation, which considers the relation between woman and her body, will include a reading room, a film-screening and an agit-disco. Kivland’s work investigates how our lives are governed by systems of order that complement, overlap and contradict one another while undergoing periods of change continually.

Apart from her activities as an artist, writer and curator, Kivland also engages in theoretical investigations, both teaching as Reader in Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam University and as a Research Associate of the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research in London. She has described her practice as one of stupid refinement, trapped in archives, libraries, the arcades, and the intersection of public political action and private subjectivity.

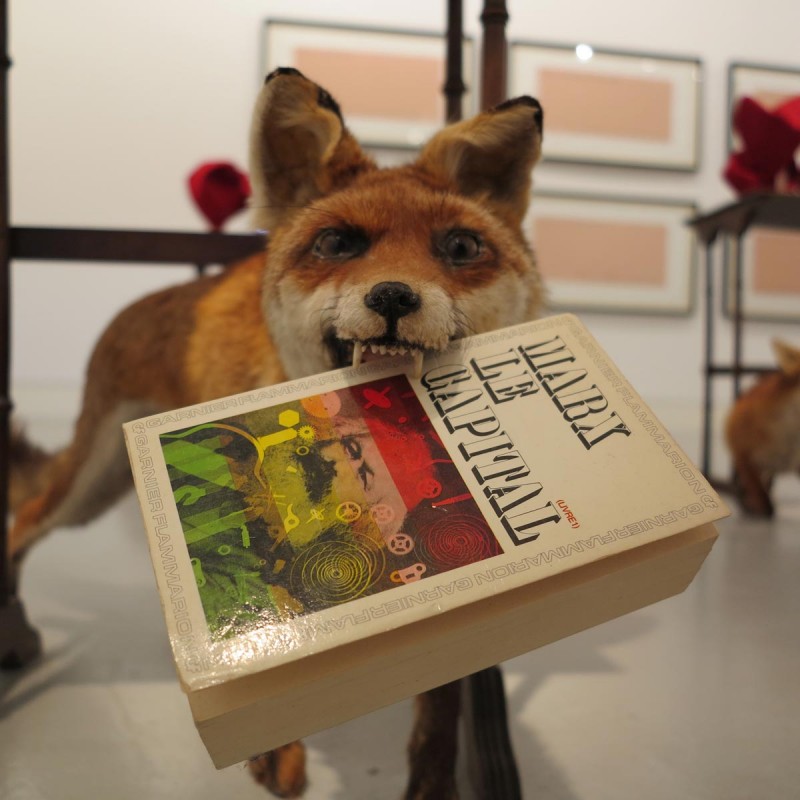

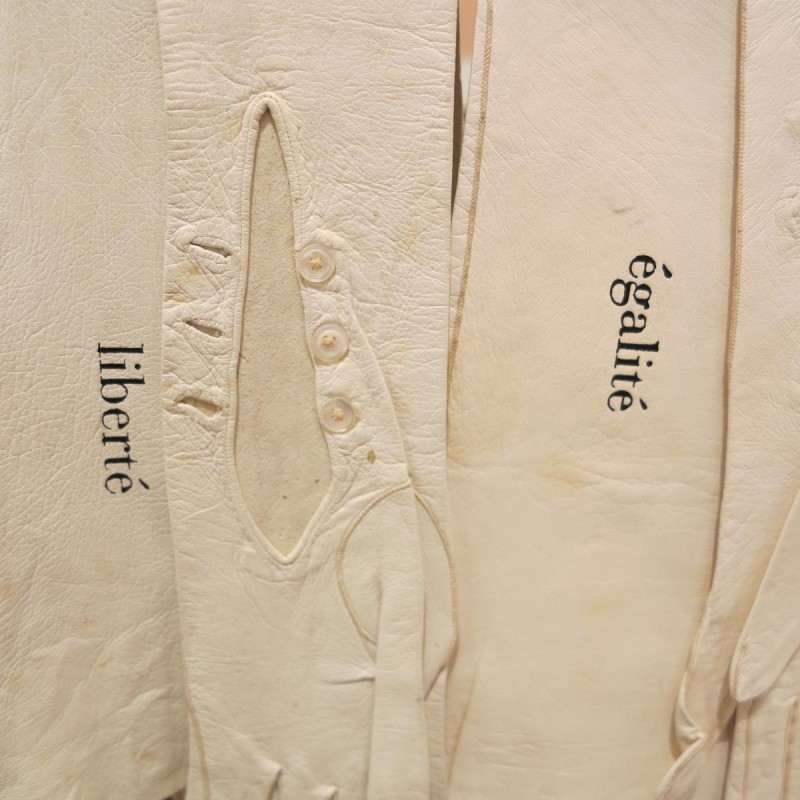

In a footnote in Capital, chapter 2: The Process of Exchange, Karl Marx writes: ‘In the twelfth century […], very delicate things often appear among these commodities. Thus a French poet [Guillot de Paris] of the period enumerates among the commodities to be found in the fair of Lendit, alongside clothing, shoes, leather, implements of cultivation, skins, etc., also “femmes folles de leur corps”.’ The English translator translates this as ‘wanton women’; Kivland would rather translate it as ‘women crazy about their bodies’, as she arranges and rearranges old and new works, addressing moments of revolution/social change. Staged as tableaux, there is a presentation of material forms in which politics and aesthetics are entwined – and lived – in the intersection of public political action and private subjectivity. Defying chronology, the works trace feminine representation: the ‘liberated’ women of 1968, Laclos’ pre-revolutionary notion of ‘la femme- naturelle’, Toussenel’s consideration of woman as mediator between man and animal, Proust’s evocation of Odette’s costume as architecture. Feminism, psychoanalysis, politics, literature (yes, all of that), and irony as a rhetorical trope inform works that explore connections between 1784, 1848, 1871, 1968, and the explosions of class struggle, often read in fashion’s detail.

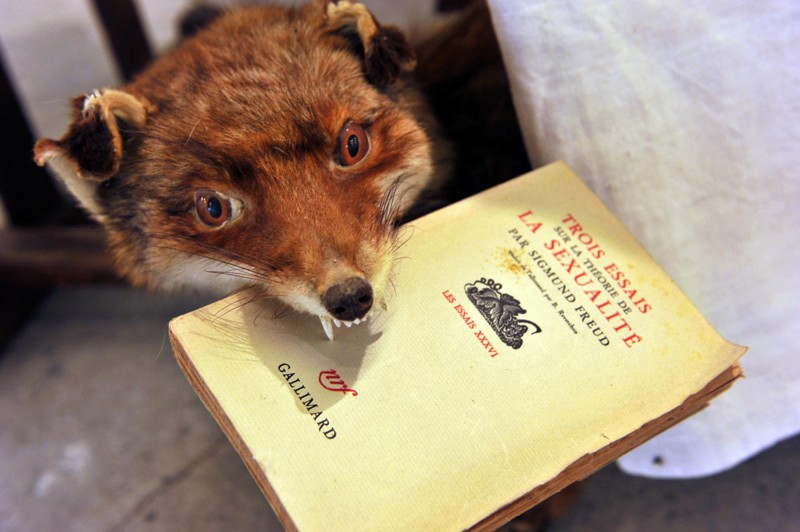

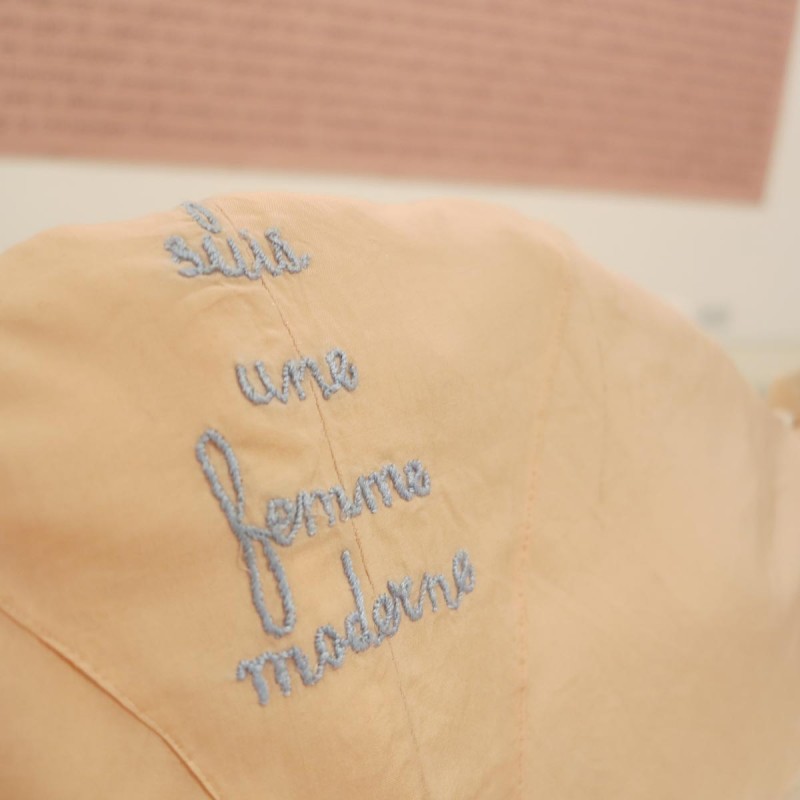

The exhibition opens with the five short texts of Le Lever, torn from a from an auction catalogue description of an engraving after a painting by Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, the son-in-law of Boucher, who, like his father-in-law, depicted the voluptuous eroticism of the ancien régime, transformed into chapters. The servant girl kneels before her mistress, holding her satin mule. Stuffed animals (aristocratic greedy squirrels who take everything from themselves, a mob of stoats, sporting Phrygian bonnets, cunning radical foxes who have read Marx) proliferate. In La Forme-valeur, Marx’s Capital is read, chapter three on exchange-value, in an attempt to find a woman speaking, yet all is found is an object speaking in the charming voice of a commodity in the chorus of goods going to market. Scent bottles (Allure) might become Molotov cocktails, the material that may be soaked and ignited is French wedding tulle, which is rather expensive. The repetitive (and as the artist is the first to admit, dull and amateur) films of Mes coquetteries follow silk-clad bodies while a voiceover recalls the radio transmissions of the Resistance and from the Underworld via the car radio of Cocteau’s film Orphée. In Encore un effort a banner carries the breathless descriptions of the new fashions for 1968, when anything goes and details place the accent on this or that part of the body and its adornment: a pair of shoes that have come off in a struggle, for example, the heel of one snapped off; a checked shirt, with two buttons undone; a light-coloured trench coat (perfect for a May day); a blouson- style jacket that allows easy freedom of movement; pale casual slacks worn with an ankle boot. Beauty is in the streets as fashion becomes democratic (or so say the houses of haute couture), while the philosopher of the boudoir extorts us once again to take action. To an assembled crowd of sensitive men and women, which petit-maître or dangerous man of principles would suggest that the only moral system to reinforce political revolution is that of libertinage, the revenge of nature’s course against the aberrations of society?

Launch Gallery