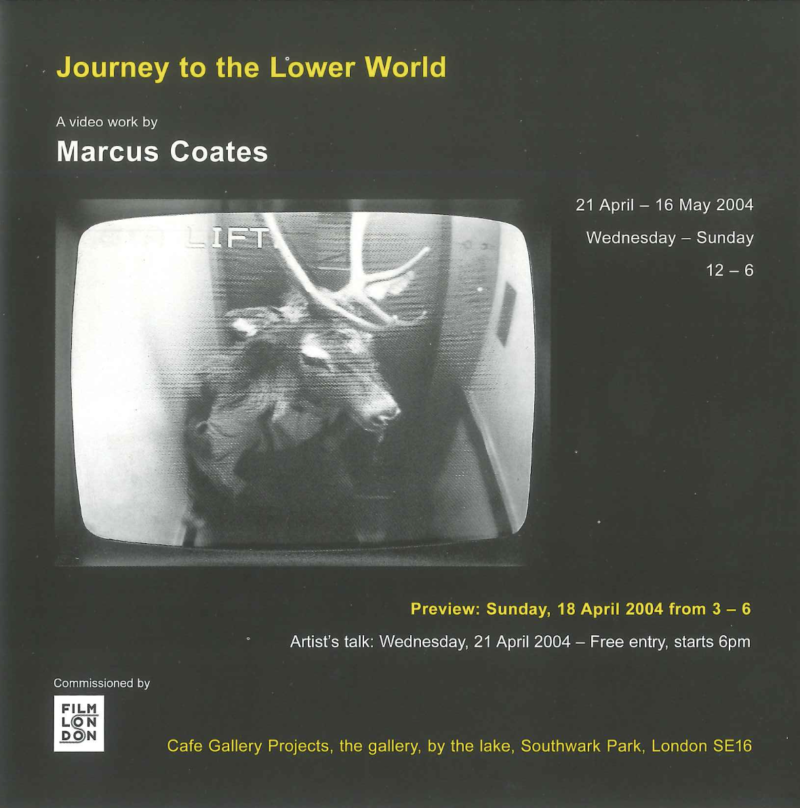

In 2004 Marcus Coates presented the London debut of his iconic work ‘Journey to the Lower World’ at Lake Gallery (when we were known as Cafe Gallery Projects /CGP London).

Coates’ influential video work sees the tenants of Liverpool’s Linosa Close guided into the anthropomorphic and ancient world of the shaman. Naturalistic and contemporary worlds meet to transform and re-discover new forms of knowledge, spirituality and community.

The work was commissioned by Film London (@film_london) and produced with Further Up in the Air and Liverpool Housing Action Trust. Marcus is represented by Workplace and Kate MacGarry, London.

Better Believing: Marcus Coates’ Journey to the Lower World

Dressed in the pelt and antlers of a wild stag, Marcus Coates prepares to make his journey to the lower world. It’s a little awkward, because the lift isn’t very big, and the antlers make it difficult to reach the button for the 18th floor, clanking against the aluminium walls and catching the fluorescent light fixture above. This also means that to go down the artist has to go up, to a small council flat in Linosa Close, a tower block scheduled for demolition, high above the Sheil Park neighbourhood of Liverpool. In a few months, this council block will make its own journey of descent, as the dynamite rigged to blow in its lower floors will draw this relic of the welfare state earthwards, with the controlled grace that makes old tower blocks appear to be merely sliding back into the earth, like the too-long-open drawer of a filing cabinet. Soon, all the residents will have moved out into the bright, clean, low-rise suburban estate that has been built to replace it. Gathered in the living room of the little flat, Coates explains to the residents, in a gently matter-of fact way: ‘I’m going to go on a journey; I’m going to go down to the lower world to converse with animal spirits, and ask them a question on your behalf, which might help you in the future.’ Coates has brought the figure of the Shaman a long way from his origins in the sub-arctic wastes of Siberia, to the secular horizon of 21st century Liverpool. His authentic enactment of the Shaman’s ritual, his sincere intention to immerse himself in the experience of another being, to become that being (he went on a weekend Shaman training course to get it right), opens a troubling and comic dialogue with the contemporary nature of spirituality and belief, of ‘community spirit’, and of how, in the absence of other strong forms of collective identity, art can become a substitute for the subjective needs of people in modern society. Before he starts his trance, Coates prepares the space; it’s a Siberian Tuvak ritual (not all Shamans are the same): Purifying the space (some light Hoovering), tying magical rattles to his shoes (his car keys), and marking out the ground by spitting (supermarket mineral water). To the beat of a Shaman’s drum (on compact disc) Coates begins his trance. ‘What is our protector?’ the residents have asked, a question both sarcastic and playful, cautious of the earnestness of Coates’ endeavour, and yet still game for a laugh, even if that laugh is honest in its anxiety about the prospect of leaving the old block for the new estate below. Belief and scepticism, trust and uncertainty, faith and apprehension. Coates sways and stamps, pacing the room, the antlers not helping very much; he utters strange calls and grunts, and it’s anyone’s guess what is going on inside his head, or where he is. Emerging from his apparent trance, he recounts his journey, imagining taking the lift to the basement, then into the bowels of the earth. A sequence of encounters with animals follows – moorhen, coot, stag… and then the vision of a Sparrow hawk, who attempts to fly but can’t, because its wing-feathers all move against each other; the Sparrow Hawk turns into a snake, and slithers away. Coates interprets this with contemporary simplicity; sticking together after their rehousing will be the residents’ greatest source of strength. In taking on the role, Coates revisits modern art’s many previous rediscoveries of the figure of the Shaman, especially the work of the German artist Joseph Beuys. Beuys’ reinvention of the Shaman was part of a broader revision of the role of art and the artist in contemporary culture, a role for which the pre-modern figure of the Shaman is ideally suited. For Beuys, the only way to resolve the troubles of society was through art, which, rather than being separated from life, might operate as a healing force, creating links between individuals, and contributing in the whole of social existence. In an earlier modernist incarnation, the artist could be a marginal figure, the individualised, romantic, intoxicated explorer of the extraordinary spectacle of modern life. But since the 1960s, and with artists like Beuys, the artist has been reconsidered as an agent of social change, an outsider figure who is nevertheless able to catalyse new relationships between individuals and society. The artist has become a kind of ‘special person’; not in terms of the objects they produce, but for the way he or she forges new relationships within culture and society. If making society better has become a constant preoccupation for contemporary artist, then art has become a site where the artist’s outsider attitude can intersect with ordinary life in ways which go beyond the norms of everyday existence. Shamanism is just one of the many rediscoveries that Western culture has made of those pre-modern identities that exemplify spiritual experience, communal harmony and a close identification with the natural world. In a society in which established faith and social institutions have broken down, previously alternative perspectives have become mainstream; psychic healing in Surrey, meditation in Maidstone . . . why not Shamanism in Sheil Park? Whether one calls it ‘counter-culture’, ‘New Age’ or ‘alternative belief’, its core messages – personal liberation, the rejection of society’s norms, and the return to a lost unity between individual, social and natural life – are now common currency. Even the Government believes that the artist can be beneficial to everyday life; determined that art and creativity can play a part in solving social problems, the artist is celebrated precisely for being ‘special’, a first amongst equals in a society in which – echoing Beuys’ declaration that ‘everyone is an artist’1 – ‘everyone is creative’2. Back at the flat, Marcus Coates, tired and a bit sweaty, chats with the residents about his journey. If artists are encouraged to play the part of latter-day Shamans, then Coates’ ritual might be art questioning it’s own Shamanic ambitions. Coates’ work has often explored the margin between mimicry and reality, between imitating another being, and losing oneself in the process. With the Shaman, this process doubles up; the artist mimics/becomes the Shaman – who himself mimics/becomes animal in order to mediate the troubles of his tribe. In doing so Coates tests how personal belief is realised as part of a community and a common culture, and closes the circuit between art and Shamanism. After all, if the residents of Linosa Close believe Coates’ ritual, and gain something from it, hasn’t Coates’ art achieved its purpose? Yet in seeing if Shamanic ritual has any application to ordinary life, Coates tests both its potentials and its limitations: No doubt his Shaman offered good advice to the residents. But Linosa Close will still be pulled down – there are limits to both the Shaman and the artist’s powers. The artist’s real role might then be to keep things, and people, open to possibilities, wary of closed certainties and yet sceptical of belief. He may be ‘for real’ or he may be a charlatan, but Coates’ earnest re-enactment of Shamanism, and art, proposes that both are only as good as the culture they inhabit, as useful as the community that gives rise to them. But making things better can only really come from people themselves; Coates’ tautological proposition is that whilst the artist can demonstrate that everyone can be an artist, that everyone can play a creative role in their situation, people can only realise this for themselves. Being a Shaman, being an artist, believing you can transform the world you are in, merely depends on whether you believe in yourself. A better form of believing.

JJ Charlesworth February 2004

1 Joseph Beuys, ‘I am Searching for Field Character’, in Art into Society, Society into Art, (ICA; London, 1974) 2 Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Culture & Creativity: The Next Ten Years, DCMS 2001, p.5